Reading Time: 12 minutes

The memorial feast of St Thomas the Apostle on 3 July does not get a mention in the Ordo this year, because it falls on a Sunday, the Lord’s Day, which takes precedence in the Roman Catholic calendar. Syro Malabar Christians and many other Syrian Churches of India consider the Apostle Thomas as their founder and so 3 July is a day of great importance in their liturgical calendar. It is of such importance that they have a special Aramaic name for the feast – Dukhrana (meaning ‘memorial’). This year marks the 1950th anniversary of the martyrdom of the Apostle Thomas.

Did St Thomas Evangelise India?

It is believed that St Thomas, affectionately called “Mar Thoma”, arrived at Kondungalloor on the Kerala coast in 52 AD. The fruit of the Apostle’s two decades of missionary work saw the establishment of more than seven communities (churches) on the south western coast of India. Unfortunately, at the end of his missionary efforts, St Thomas met with hostility and was martyred at Mylapore near Chennai, in 72 AD. The place of his martyrdom has a continuous history of veneration. Acknowledging this, Pope Paul V erected the diocese of Mylapore in 1606 according to the ‘Padroado’ agreement with the king of Portugal. The reason was that it was there the body of St Thomas lay buried. In 1956, Pope Pius XII raised Mylapore church to the status of a Basilica Minor. A visit to the tomb by Pope St John Paull II during his apostolic visit in 1986 highlighted the Thomas tradition once again. Along with these, there is a long and consistent history of ‘Nazarani’ (Christian) presence on India’s south-western coast. Over the centuries, India’s Christians have developed their own rituals and practices, adapting them to their local situation. However there are sceptics who doubt the story of St Thomas landing on the Kerala coast.

The most controversial apparent scepticism was in the remarks by Pope (emeritus) Benedict XVI in 2006. In a pronouncement at St Peter’s Square, he spoke in a manner seemingly taking away from St Thomas the title ‘Apostle of India’. Pope Benedict proposed that Thomas preached in Syria, Persia, and then North Western India or Pakistan. Fr George Nedungattu from the faculty of the Oriental Pontifical Institute in Rome, pointed out that the pope’s notion was probably wrong – South India was in fact evangelised by St Thomas. Dr Pius Malekandathil of the Centre for Historical Studies at Jawaharlal University in New Delhi argued that Thomas may have made two trips to India, first by the silk road route, reaching the current state of Maharashtra in north-western India. He may then have gone back to Jerusalem to attend the Council of Jerusalem in 48 AD before sailing to India’s south via the monsoonal trade route which was active at that time. In any case, it is generally agreed that the roots of the early Church in India trace back to Thomas and that he the patron of India. Discussions originating from the comments made by Pope Benedict XVI ended up reaffirming Thomas’s title as “the Apostle of India” and the Pontiff later referred to Thomas using that title. Since then, the Ordo used in Australia also began referring to Thomas in this way

‘Doubting Tom’ – or something more?

Who was Thomas? Was he a ‘Doubting Tom’? There are a number of reference to Thomas in the New Testament. Listing the apostles, the Synoptic Gospels place him next to Matthew (Mt 10:3; Mk 3:18; Lk 6:15). Listing the Apostles gathering in Jerusalem after the ascension of the Lord, the Acts of the Apostles place Thomas after Philip (Acts 1:13). John’s Gospel is different and reveals more about his personality.

John’s Gospel is the fruit of meditation by his community on the mystery of Christ. In the last verses of chapter 20, John gives the reason why he has written about this appearance of Jesus. “These are recorded so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name,” he writes. (Jn 20:31) John’s Gospel was probably written about 60 years after Jesus’s death and resurrection. Most of his audience had not met Jesus personally and, like us, they had to rely on the testimonies of the apostles or their disciples to come to faith in Christ. To them, John says it does not matter whether they have not seen Jesus personally, because the risen Christ told Thomas that “blessed are those who believe although they have not seen [him]”.

John’s narrative reveals something interesting about Thomas: after Jesus’s death and resurrection all the disciples – except Thomas – were terrified of the outside world until Jesus appeared to them and made them believe. Although we do not why, while the other disciples were terrified of the outside world and locked themselves in a room, Thomas had the courage to go out.

An earlier chapter in John’s Gospel also gives an insight into both Thomas’s courage and great loyalty to his master Jesus.

While Jesus was on his way to Jerusalem, news reached him that his friend Lazarus was dying. Jesus, in spite of being a good friend, did not hurry to Bethany which was situated near Jerusalem to help Lazarus. The disciples, though puzzled by His apparent lack of concern, concluded that he was afraid to visit Bethany as it was too close to Jerusalem where the hostile Jews were waiting to catch and kill Him. The synoptic Gospels also refer to this danger (Mt 20:18-19; Mk 10:32; Lk 18:31-33). But two days later, Jesus announced his intention to go to Bethany. This time the disciples asked, “Master, recently the Jews wanted to stone you. Are you going there again?” (Jn 11:8). They were virtually asking Jesus whether he was mad. At this, Thomas shows his mettle. As John record: “Then Thomas, called the Twin, said to his fellow disciples “Let us also go that we may die with him”” (Jn11:16).

After Jesus’s resurrection, a man with such loyalty could not bear the news that Jesus had appeared to his companions in his absence. A heavy-hearted Thomas insisted on meeting Christ personally. More than doubt, it was very likely his grief that asked for Jesus’s vindication of his reseurrection. A week later, when Jesus appeared again and called Thomas to examine the wounds and marks of the crucifixion, Thomas was freed from his gried. Overjoyed, he made the profession of faith, “My Lord and my God” (Jn 20:28), which has reverberated down through the ages. According to the gospels, Peter is the only other person to make such a profession. Thomas’s response is also akin to that of Peter who said, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (Cf 6:68).

John’s Gospel also includes an intervention by Thomas at the Last Supper. Then, when Jesus announced that he was going to prepare a place for his disciples where they could reach and find him, Thomas intervene, asking, “Lord, we do not know where you are going; how can we know the way?” (Jn 14: 5). This led to the revelation given by Jesus that “I am the Way, and the Truth and the Life” (Jn 14: 6). Thus, Thomas became an instrument of Jesus’ revelation of his divine identity.

The loyalty of Thomas to his master, his profession of faith that Jesus is Lord and God, and his intervention at the Last Supper are indicative of his intimacy with Jesus. Perhaps it was this intimate closeness to Jesus that earned him the nickname “Twin”, as if he was a twin brother of Jesus. John’s Gospel refers to Thomas using this term several times (cf. Jn 11: 16; 20: 24; 21: 2). In fact, the name ‘Thomas’ is derived from a Hebrew root, ‘ta`am’ which means ‘twin’ or ‘paired.’ Thus, Thomas was far from being a “doubting Tom”. He was an apostle with a deep rooted faith and trust in Jesus. It must have been his courage that made him a missionary to the far country of India.

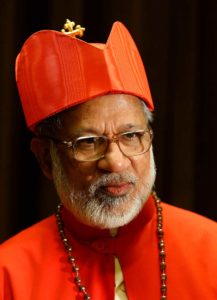

The Liturgy of St Thomas Christians

The Syro-Malabar Church is the largest of the churches claiming the legacy of St Thomas the Apostle. The Christians of the Malabar/Malankara coast of India shared a liturgy with the Chaldean Church, although it was also eventually modified to accommodate local cultural elements sa well. The history of the Church in India is continuous from the St Thomas until the Padroado missionaries came to the Indian coast in the 16th Century under the agreement between the king of Portugal and the Pope. However the misgivings between the native Church of India and the newly-arrived missionaries escalated into conflict, so much so that in a pseudo synod held at Udayamparoor (Diamper) in 1599, most of the liturgical books used by the St Thomas Christians were burned and destroyed. Since then, only a highly-Latinised version of the liturgy has been available to the Syro-Malabarese, although a restoration of the integrity of the original liturgy and the identity of the Syro-Malabar Church has been slowly undertaken. The revision of the liturgy in 1962 was a breakthrough, though the influence of the Roman liturgy was still very prevalent in the new Taksa (Missal). It was revised again in 1968, with substantial changes being made again in 1986. By then there were two differing viewpoints emerging: one group wanted to retain many of the modern developments of the Roman Liturgy adopted by the Syro-Malabar Church, while the other wanted to reform the liturgy according to pre-Padroado historical roots. One of the points of contention is whether the presiding priest should face the congregation or not during Mass. Lately there have been ugly scenes of public demonstrations in the name of liturgical reform.

In the Roman Liturgy, the presiding priest stands on one side of the Altar with the congregation on the other side. The idea is that the presider and the congregation are gathering around the Altar for the Mass which is both a Holy Sacrifice and a Sacred Meal. However the Syro-Malabar liturgy and rubrics seek to evoke a pilgrimage to the Parousia, the end of all time. In the Syro-Malabar liturgy the priest-celebrant is like the resurrected Jesus leading the faithful towards the Parousia. To represent the joy of the resurrection, the priestly vestments are ornate with joyful colours. This means there are no seasonal liturgical colours in Syro-the Malabar liturgy. Meanwhile, the pilgrim journey is manifested through the inter-related celebration of six events – the Nativity-Epiphany, the Resurrection, Pentecost, the Transfiguration, the Exaltation of the Cross and the Parousia.

The arrangement of the sacred furniture in a Syro-Malabar church takes its inspiration from Jewish synagogues. For the first part of the Mass, the celebration of the Word, the priest is positioned at the ‘Bema’ which is ideally placed in the middle of the nave, like the bema in a synagogue. But the bema in synagogues are not the same as in churches. The bema in the church is like a smaller altar in front of the main Altar, whereas the Jewish bema would be a raised platform with decorative guard rails. The Gospel is read from the ‘bema’, and always by the principal celebrant, who remains there to preach as well. Other scripture readings have their own lecterns, ideally separate ones, for the Old and New Testament readings. Other movements in the liturgy also have their own uniqueness, for example, the offertory procession is done by the celebrant priest(s) (and not by the congregation) from the tables of preparation on the sanctuary to the Altar. Another observation would be the chanting of psalms, praises, and antiphons all through the Mass. Each Mass is like a joyous journey of the faithful, chanting and praising God.

![[HOMÉLIE] À Thomas, Dieu se révèle par sa miséricorde](upload/sources/96741576254947.jpg)